Ah, to have the command of a native speaker! To be able to say exactly what you mean, without having to think about what you want to say, and without making mistakes! If only I could be that good, but I never will!

Such is the lament of almost everyone learning a language. No matter how we advance in our learning, no matter how confident we get, whenever we see a native speaker in full flow we’re at once impressed and dismayed. They remind us of how far we have to go, and the gap that, realistically, will always exist between a native speaker and a learner, unless they completely immerse themselves in the language.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. As I’ve said before, native speakers are prone to often-surprising mistakes in their own language. In many cases, these are grammar mistakes, caused partly by the fact that English grammar doesn’t tend to be taught with any degree of rigour in Anglophone countries. The main reason we make mistakes though, is that we acquire our native language first through listening, and then speaking. Reading and writing come much later, and because they require the use of letters, accuracy is crucial to both. And yet, even when we’ve mastered the basics of reading and writing, most of our exposure to language remains aural, and our production of it, oral.

This is why, for example, many people will write your instead of you’re (I actually just typed your instead of you’re: it’s easy to do!); because when we hear someone say You’re great, and your blog is amazing (you get used to it after a while), you don’t see or hear a difference between You’re and your. Added to this, is the fact that we don’t always speak very clearly. My “teacher voice,” for example, is much louder, slower, and clearer than my voice when I’m speaking with other native speakers. Then I mumble, don’t use complete sentences, let words run into each other, and speak quite quickly. The result of this is that we don’t always hear things very clearly, and are particularly prone to mishearing commonly-used multi-word phrases. It’s the same concept behind mishearing song lyrics: the longer the phrase, the more opportunities we have for misunderstanding it. Let’s have a look at some of the most common phrases that people get wrong…

For all intensive purposes instead of for all intents and purposes: this one is quite understandable, given that when spoken by a native speaker, the sole difference is the /n/ or /v/ sound before purposes. Also, people probably don’t expect to hear the word intents, because it’s not so common. Their brains therefore instead translate intents and as intensive, as they expect to hear the latter more frequently. And, having both intents and purposes in the same phrase might seem redundant. Personally though, I think it’s ok, because you can distinguish between intents and purposes: the former has a mind behind it, whereas the latter is more general, and could be impersonal or abstract. But most importantly, saying for all intents or for all purposes would be too short: using both words gives the phrase a nice rhythm.

Play it by year instead of play it by ear: Again, this is all about similarity of sound. More than similarity in fact, as these two actually sound identical. Now, if you’re an English speaker, you might disagree with that, and point out the y in year as the big difference. And you might be pronouncing them both and contrasting them right now. But when you look at the two together, you’re going to emphasise the y in year to distinguish them. But try to think about how you would say them in real life. When we’re speaking naturally, we don’t leave a gap between by and ear, because that would lead to an awkward glottal stop. What we actually do is include something called an intrusive /j/, to link the two together. So, we add a /j/ sound (which sounds like the sound of the letter y, not j, confusingly) to ear (something you’ve been doing from early childhood, so you don’t notice it: but say the phrase with the y, and then with a slight gap between by and ear, to notice the difference) so that by ear and by year are identical in sound. And of course, play it by ear might not make sense to a lot of people, so they might assume the word is year. But it refers to playing music without sheet music, thus the meaning of the phrase: to operate without a plan.

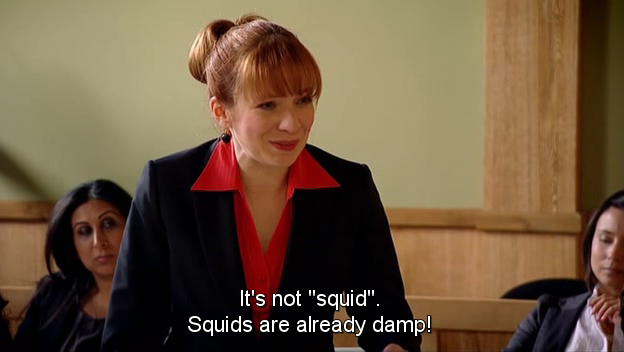

A damp squid instead of a damp squib: an easy one here too—to quote Roy: What’s a squib!? Well, a squib is a small type of firework, but the word is more commonly used now in terms of special effects, to refer to the little explosives that go off on someone’s body to simulate being shot in movies and TV. But most of us don’t know that word, so assume the word is squid. But of course…

The Ioneer Hospital instead of Eye and Ear Hospital: this is one that can cause people quite a degree of embarrassment when they realise they’ve been making a mistake. Again, it’s somewhat understandable because in natural speech, ioneer and eye and ear sound identical. We usually drop the d, and link the three words together. But of course, ioneer is not an actual word. But it’s curious that so many of assume it is, that it’s just some medical term, but we don’t need to know what it means, because the doctors know, and they’ve got years of ioneer training and experience to make us better. And I don’t mean to mock here, because I understand that. We can’t know every word in the language, and what they all mean. And we can’t know everything about medicine either, even if we’re being treated, because that’s a lot of information, and we therefore leave it up to doctors to know what they’re doing, and how to successfully operate an ioneer.

So if you’ve made any of these errors, well, now you know the right way, and can subtly start using the correct forms without anyone (hopefully) noticing. And I wouldn’t worry anyway: the nature of natural connected speech means that people probably didn’t notice anyway. The mistakes sound so similar to the correct forms, and, if we know what the correct forms are, our brain will expect to hear them and we therefore will think we hear them, even if someone’s getting it wrong. So for all intensive purposes, you’ve got away with it!

I think you have a better mastery of the language than a lot of native speakers – we really DON’T learn it in school! I never had any grammar lessons past 8th grade, and most people seem to forget what they learned back then.

A squib, of course, is a person born with magical blood but with no magical ability. Source: J.K. Rowling

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I was always a grammar nerd, but training to teach English really opened my eyes up to how little I still knew about it. I like that use of squib, feels quite appropriate 😊.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I say scrap “for all intents and purposes” while, even if used correctly, it has become cliche. And if rhythm is what you’re worried about, it’s only rhythmic to our ears because it’s been so over used (and abused.) By the way, do you teach English in China?

LikeLike

I know what you mean, it’s definitely overused. I think if it were only used when it was useful it’d be better, as people tend to use it when it doesn’t add anything to what they’re saying. I’ve actually only taught English to visiting students in Ireland.

LikeLike

You’re right: people aren’t learning grammar as they should. Twenty odd years ago I read where the public school system in Ontario dropped grammar as a subject because it “hinders the flow of creative writing.” I’m glad the great writers like Dickens didn’t seem to be overly restricted by grammar rules.

One common misquote I hear is “old timers’ disease” instead of Alzheimer’s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think a lot of people create a false binary between using proper grammar, and writing creatively. True, a lot of the great writers don’t always obey some specific rules, but people forget that grammar is about the fundamental structure of the language, and most good writers at least unconsciously have good grammar (probably picked up from reading).

LikeLike

[…] on Isle in the former, and love in the latter. Still though, the difference is neglible, and for all intents and purposes they sound […]

LikeLike

[…] so, well, free with how we use the word free in English. I’m sure you’ve been on tenterhooks since then, so let’s […]

LikeLike